Saturday, March 22, 2014

#MRA14 in tweets

Last weekend I attended the Michigan Reading Association conference for the third year in a row, and as always it was an inspiring weekend of learning and friendship. Rather than try to put into words what an amazing weekend I had, I'd rather just let my tweets do the talking:

Thursday, March 20, 2014

The day the music died

I started out my college career as a music education major. My second semester I encountered a professor who broke me. He told me I had no talent and that I'd never make a career in music.

So one day I left a note on his studio door telling him I hope he is more gentle with students like me in the future, quietly dropped his class, and left the music program.

Before I turned my back on music for good, I decided for my own pride that I was going to prove him wrong. The semester I dropped out of his class, he assigned me Franz Schubert's Moment Musicaux No. 1 in C Major and proceeded to do nothing but tell me what I terrible job I was doing and how I'd never learn the piece. So I decided when I dropped out of the music program that I was going to take that piece to my longtime piano teacher -- who always nurtured my love and passion for the piano rather than tore me down -- and ask her to help me learn it for the upcoming American Guild of Music competition.

Even though I hated the piece (and I was never one who was motivated to learn pieces I hated), I was determined to learn it and prove that professor wrong. Well I did more than learn it. I won 3rd place at the competition that year.

Despite my success at the competition, the damage had already been done. That professor had sullied the one thing in my life that gave me solace and comfort.

Fifteen years later and the scars are still there. They will never fade. They will always be a part of me.

I still own a piano, but I very rarely sit down to play anymore. Every so often I'll hear a piece I used to play, like Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata or Chopin's Waltz in C# Minor, and that is a small impetus to make me want to sit down and play for a half hour at a time, but the passion and the drive I once had is completely gone.

So why share this story on my blog? I'll let you make those connections. I'm pretty sure it's fairly obvious. But just in case it isn't, I will leave you with one final question: are we building our students up or tearing them down?

So one day I left a note on his studio door telling him I hope he is more gentle with students like me in the future, quietly dropped his class, and left the music program.

Before I turned my back on music for good, I decided for my own pride that I was going to prove him wrong. The semester I dropped out of his class, he assigned me Franz Schubert's Moment Musicaux No. 1 in C Major and proceeded to do nothing but tell me what I terrible job I was doing and how I'd never learn the piece. So I decided when I dropped out of the music program that I was going to take that piece to my longtime piano teacher -- who always nurtured my love and passion for the piano rather than tore me down -- and ask her to help me learn it for the upcoming American Guild of Music competition.

Even though I hated the piece (and I was never one who was motivated to learn pieces I hated), I was determined to learn it and prove that professor wrong. Well I did more than learn it. I won 3rd place at the competition that year.

Despite my success at the competition, the damage had already been done. That professor had sullied the one thing in my life that gave me solace and comfort.

Fifteen years later and the scars are still there. They will never fade. They will always be a part of me.

I still own a piano, but I very rarely sit down to play anymore. Every so often I'll hear a piece I used to play, like Beethoven's Moonlight Sonata or Chopin's Waltz in C# Minor, and that is a small impetus to make me want to sit down and play for a half hour at a time, but the passion and the drive I once had is completely gone.

So why share this story on my blog? I'll let you make those connections. I'm pretty sure it's fairly obvious. But just in case it isn't, I will leave you with one final question: are we building our students up or tearing them down?

Tuesday, March 11, 2014

Dear people who have never taught before: stop saying class size doesn't matter

Valerie Strauss recently posted on her Washington Post blog The Answer Sheet about a study that was published that finally shows class size does matter -- small class size that is.

I get so frustrated with people who have never taught in a classroom saying that class size doesn't matter and that any teacher worth his salt could teach kids no matter how large the group. Here's the thing: even if that were true, just because a teacher CAN teach a whole boatload of kids doesn't mean she SHOULD. There's this little issue we have in this country with teacher turnover, and when I say little issue, I really mean big issue.

More students in the classroom means more work for the teacher, means more burn out, means more teachers quit. Let's not forget that nearly 50% of teachers leave the profession within the first five years. We're so obsessed with numbers and data in this country so we forget that teachers and students are HUMAN. This issue isn't just about numbers and what physical, mental, and emotional feats you can subject a great teacher to just because the data shows great teachers can handle 30+ students at a time. This is about ethics. This is about quality of life. Even teaching a total of 60 students -- about 20-22 students per class -- I burned out. That's a lot of papers to grade, lessons to plan, personalities to learn, and interests to cater to. I can't even imagine what a high school teacher with 5 or 6 classes of 30-40 high needs students must endure.

So it's nice to finally see that studies are showing what teachers knew all along: small class size matters.

Let's take a note from this tweet sent out by high school teacher Jeannette Haskins:

It's amazing what deep meaning can be conveyed in just a simple 140 character tweet. Jeannette's words are so true. If we don't produce environments for our teachers to thrive, our students won't either.

I get so frustrated with people who have never taught in a classroom saying that class size doesn't matter and that any teacher worth his salt could teach kids no matter how large the group. Here's the thing: even if that were true, just because a teacher CAN teach a whole boatload of kids doesn't mean she SHOULD. There's this little issue we have in this country with teacher turnover, and when I say little issue, I really mean big issue.

More students in the classroom means more work for the teacher, means more burn out, means more teachers quit. Let's not forget that nearly 50% of teachers leave the profession within the first five years. We're so obsessed with numbers and data in this country so we forget that teachers and students are HUMAN. This issue isn't just about numbers and what physical, mental, and emotional feats you can subject a great teacher to just because the data shows great teachers can handle 30+ students at a time. This is about ethics. This is about quality of life. Even teaching a total of 60 students -- about 20-22 students per class -- I burned out. That's a lot of papers to grade, lessons to plan, personalities to learn, and interests to cater to. I can't even imagine what a high school teacher with 5 or 6 classes of 30-40 high needs students must endure.

So it's nice to finally see that studies are showing what teachers knew all along: small class size matters.

Let's take a note from this tweet sent out by high school teacher Jeannette Haskins:

We owe it to our students to Thrive so they can too. #engchat

— Jeannette Haskins (@wjteacher) March 10, 2014

It's amazing what deep meaning can be conveyed in just a simple 140 character tweet. Jeannette's words are so true. If we don't produce environments for our teachers to thrive, our students won't either.

Monday, March 10, 2014

On education, scoring, and... skating?

When I was fourteen, I started watching figure skating religiously. It was 1994 and I was in 8th grade. I'm sure you can imagine what the instigating factor for my sudden interest in skating was: the Nancy Kerrigan/Tonya Harding scandal for the 1994 Olympics.

The human drama of that moment in history is what led me to watch, but eventually I realized there was so much this sport had to offer, which is why I continue to watch it twenty years later. As a girly-girl who loved sequins and sparkles, I of course loved seeing the glamorous costumes, but that superficial fascination eventually evolved into something much deeper. Skating is not just a sport. It is also an art. The opportunity skaters have to create, not just triumphant feats of athleticism, but also brilliant moments of artistry and emotion, sets it apart from all the other Olympic sports. When I watch a performance like Michelle Kwan's 2003 World Championship long program, I don't care about the jumps. Yes, landing all those jumps punctuates her brilliant performance, but she did more than just land jumps. She created a Moment.

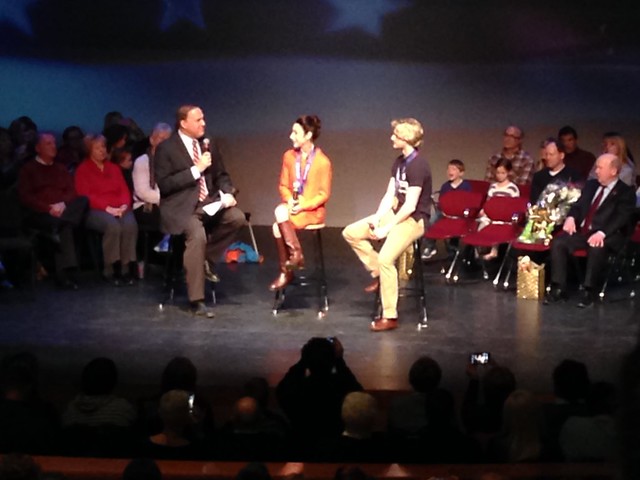

So fast forward twenty years from 1994 when I first became a fan of skating to today, March of 2014. I live in Canton, Michigan, which happens to be where the Olympic gold medal ice dancing team of Meryl Davis and Charlie White train. Yesterday was their welcome home celebration at a local theater, and at one point in the program, the emcee asked Meryl and Charlie how their coach, Marina Zoueva, has helped make them the champions they are today. Meryl's response really struck me. Instead of saying something like, "Marina is a great technician and really taught us proper technique," she instead said something very simple and yet profound: "We've learned about life and art from Marina." Marina has coached and choreographed for many skating champions. She is known for creating stunning, memorable, and heartfelt programs as well as pushing and bringing out of her skaters more than they thought was possible. She doesn't just focus on technique, but really tries put the heart and soul of her skaters in their performances.

theater, and at one point in the program, the emcee asked Meryl and Charlie how their coach, Marina Zoueva, has helped make them the champions they are today. Meryl's response really struck me. Instead of saying something like, "Marina is a great technician and really taught us proper technique," she instead said something very simple and yet profound: "We've learned about life and art from Marina." Marina has coached and choreographed for many skating champions. She is known for creating stunning, memorable, and heartfelt programs as well as pushing and bringing out of her skaters more than they thought was possible. She doesn't just focus on technique, but really tries put the heart and soul of her skaters in their performances.

Meryl's comment about Marina really struck me because it reminded me of the things all great teachers do for their students. No matter what quest you are pursuing: sport, education, music, or writing, all great teachers help their pupils move beyond skill into something much bigger than themselves.

And this is precisely what breaks my heart about our educational climate today. In their quest for American students to have the best "technical merit" (to use a skating term), educational policymakers have completely reformed the "artistic impression" out of our schools, which is the heart and soul of a performance in skating, and in the case of education, it's what makes our students and teachers unique individuals.

I don't want to watch a skating performance that is all skill and no heart, and I certainly don't want to teach in a classroom that is that way either. But if you give me scripted lessons, if you force me to teach to a test, and you whittle away any sense of joy or excitement from the learning process, you can be sure that not only will the artistic impression suffer, but the technical merit will too. There has to be passion in order for there to be excellence, and I fear that we're forgetting that like all great performances, it's the passion that creates the Moment, not the technique. And in school, if we don't create opportunities for our students to learn about life and art, education will not be a goal students want to pursue. So no matter how much you mandate and test them to death, all you will do is create a piecemeal set of skills and no artistry to be able to create magical Moments in the life of a child.

The human drama of that moment in history is what led me to watch, but eventually I realized there was so much this sport had to offer, which is why I continue to watch it twenty years later. As a girly-girl who loved sequins and sparkles, I of course loved seeing the glamorous costumes, but that superficial fascination eventually evolved into something much deeper. Skating is not just a sport. It is also an art. The opportunity skaters have to create, not just triumphant feats of athleticism, but also brilliant moments of artistry and emotion, sets it apart from all the other Olympic sports. When I watch a performance like Michelle Kwan's 2003 World Championship long program, I don't care about the jumps. Yes, landing all those jumps punctuates her brilliant performance, but she did more than just land jumps. She created a Moment.

So fast forward twenty years from 1994 when I first became a fan of skating to today, March of 2014. I live in Canton, Michigan, which happens to be where the Olympic gold medal ice dancing team of Meryl Davis and Charlie White train. Yesterday was their welcome home celebration at a local

theater, and at one point in the program, the emcee asked Meryl and Charlie how their coach, Marina Zoueva, has helped make them the champions they are today. Meryl's response really struck me. Instead of saying something like, "Marina is a great technician and really taught us proper technique," she instead said something very simple and yet profound: "We've learned about life and art from Marina." Marina has coached and choreographed for many skating champions. She is known for creating stunning, memorable, and heartfelt programs as well as pushing and bringing out of her skaters more than they thought was possible. She doesn't just focus on technique, but really tries put the heart and soul of her skaters in their performances.

theater, and at one point in the program, the emcee asked Meryl and Charlie how their coach, Marina Zoueva, has helped make them the champions they are today. Meryl's response really struck me. Instead of saying something like, "Marina is a great technician and really taught us proper technique," she instead said something very simple and yet profound: "We've learned about life and art from Marina." Marina has coached and choreographed for many skating champions. She is known for creating stunning, memorable, and heartfelt programs as well as pushing and bringing out of her skaters more than they thought was possible. She doesn't just focus on technique, but really tries put the heart and soul of her skaters in their performances.Meryl's comment about Marina really struck me because it reminded me of the things all great teachers do for their students. No matter what quest you are pursuing: sport, education, music, or writing, all great teachers help their pupils move beyond skill into something much bigger than themselves.

And this is precisely what breaks my heart about our educational climate today. In their quest for American students to have the best "technical merit" (to use a skating term), educational policymakers have completely reformed the "artistic impression" out of our schools, which is the heart and soul of a performance in skating, and in the case of education, it's what makes our students and teachers unique individuals.

I don't want to watch a skating performance that is all skill and no heart, and I certainly don't want to teach in a classroom that is that way either. But if you give me scripted lessons, if you force me to teach to a test, and you whittle away any sense of joy or excitement from the learning process, you can be sure that not only will the artistic impression suffer, but the technical merit will too. There has to be passion in order for there to be excellence, and I fear that we're forgetting that like all great performances, it's the passion that creates the Moment, not the technique. And in school, if we don't create opportunities for our students to learn about life and art, education will not be a goal students want to pursue. So no matter how much you mandate and test them to death, all you will do is create a piecemeal set of skills and no artistry to be able to create magical Moments in the life of a child.

Wednesday, March 5, 2014

Every day should be Read Aloud Day

Today is World Read Aloud Day. March is also Reading Month. While I love any excuse to celebrate reading, I also think every day should be read aloud day and every month should be reading month. Literacy isn't something we should just celebrate every once in a while. It is something that should be done with great joy and gusto every day of the year. By all means, let's use these opportunities to bring to light the importance of pleasure reading and shared reading experiences on this day and this month. But let's not reduce them to something we only do every once in a while, or God forbid, once a year.

So teachers, use this day to do something extra special: find an author to Skype with your class, have older students come and read to younger students, but please don't make the act of reading for pleasure or reading aloud a special occasion. These are experiences that are needed on a regular basis for students of ALL ages, not just little ones.

So teachers, use this day to do something extra special: find an author to Skype with your class, have older students come and read to younger students, but please don't make the act of reading for pleasure or reading aloud a special occasion. These are experiences that are needed on a regular basis for students of ALL ages, not just little ones.

Tuesday, March 4, 2014

Walking the talk

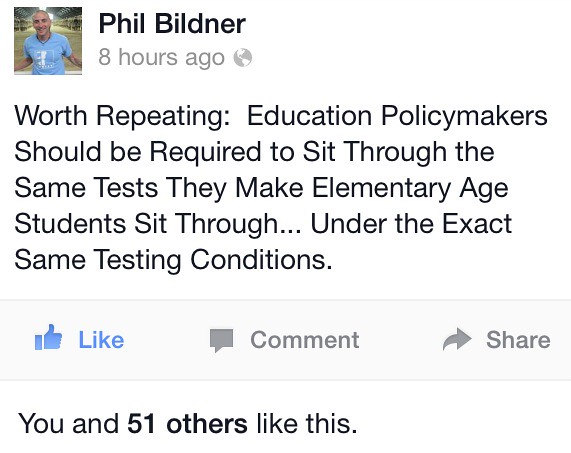

Today on Facebook author and former teacher, Phil Bildner, posted something that I wish more people in educational authority would consider:

Here's the thing: as I evolved as a teacher, I soon became aware of the fact that some of the work I was giving my students was mindless busywork. So you know what I did? I started doing the assignments I doled out to my students. If I wasn't willing to do them myself, then I certainly wasn't going to assign them. It made a huge difference in not only what I assigned, but it gave students more respect for the work I required of them.

What if this were true in the laws we create for education? I still vividly remember sitting through a session at the NCTE convention in November where Temple Grandin was presenting about the autistic brain. She is such a powerful presence in speaking out, not only for autism, but for education in general. She had a FANTASTIC idea for lawmakers. She wants to see the show Undercover Boss become Undercover Legislator. Think of all the changes that could be made in education if people in power actually chose to act with empathy and truly see what these "reforms" are doing to our students and teachers.

So until educational policymakers are willing to roll up their sleeves and get their hands dirty, experiencing some of this actual mind-numbing work that is required of both teachers and students in schools today, we're never going to see change for the better.

Here's the thing: as I evolved as a teacher, I soon became aware of the fact that some of the work I was giving my students was mindless busywork. So you know what I did? I started doing the assignments I doled out to my students. If I wasn't willing to do them myself, then I certainly wasn't going to assign them. It made a huge difference in not only what I assigned, but it gave students more respect for the work I required of them.

What if this were true in the laws we create for education? I still vividly remember sitting through a session at the NCTE convention in November where Temple Grandin was presenting about the autistic brain. She is such a powerful presence in speaking out, not only for autism, but for education in general. She had a FANTASTIC idea for lawmakers. She wants to see the show Undercover Boss become Undercover Legislator. Think of all the changes that could be made in education if people in power actually chose to act with empathy and truly see what these "reforms" are doing to our students and teachers.

So until educational policymakers are willing to roll up their sleeves and get their hands dirty, experiencing some of this actual mind-numbing work that is required of both teachers and students in schools today, we're never going to see change for the better.

Sunday, March 2, 2014

Reading about Langston Hughes made me think about what CCSS means for our students

As I was reading through a few of my old posts that I tagged under "teaching" at my other blog A Foodie Bibliophile in Wanderlust, I came across this one that I posted a little over a year ago, on February 17, 2013, that I want to re-post here because I didn't have this blog yet. The message of this post really rings true to the message of this blog.

*~*~*~*~*~*

I'm sitting here in my home office on this lazy Sunday afternoon (lazy only because it's midwinter break and I don't have to go to work tomorrow) reading Free to Dream: The Making of a Poet, a biography of Langston Hughes (my favorite poet of all time), and I am struck by his educational background. While Hughes did very well in primary school and high school and was praised by his teachers for his love of learning, Hughes, one of our most celebrated American poets, was a college dropout. His first attempt at college was a failure. He went to Columbia University on his father's dime, and after one year decided that he preferred to read books and attend lectures instead of go to class.

I'm struck by this new piece of information I learned about Hughes today because, by all intents and purposes, he should have been a model student: he loved learning, did well all throughout his K-12 education, and was often recognized for his writing prowess by his teachers and classmates. If that's not a formula for someone who should succeed in college, then I don't know what is.

But that's just it. Education can't be whittled down to a formula - numbers to crunch, multiple choice questions to answer. By today's educational reformers, Hughes would be considered a failure. Politicians would deem him a product of a failed system and no doubt his teachers would be blamed (and perhaps fired) for his inability to understand physics and trigonometry, which were the classes he chose to skip and ultimately drop out of Columbia.

But in the 1920s, Hughes used his passion for writing and poetry to seek out like-minded, accomplished people who took him under their wing and nurtured his passion and talent, which we now know turned him into one of the most beloved writers in all of American history. I continue to wonder how people responsible for making decisions about education today can be so narrow minded and refuse to see past the numbers and into the minds and hearts of our students. While we're busy trying to "race to the top", students' needs and talents are disregarded. (Does anyone else see the irony in the fact that Arne Duncan has deemed "No Child Left Behind" a failure yet, with a name like "Race to the Top", the initiative which he created to replace NCLB, isn't the very nature of a race to leave people behind?)

So as the Common Core State Standards are asking me to make my students

"college and career ready" and turn them into good little test-takers, I

can't help but know in my heart that there are much more important

things we should be focusing on, like nurturing passions and talents,

showing students we care about them as people, and teaching them the

importance of lifelong learning for their future instead of the desire

for all A's on their report card and good standardized test scores.

Despite the fact that CCSS architect David Coleman infamously told an

audience of educators in 2011, "As you grow up in this world, you

realize people really don't give a $#!% about what you feel or what you

think," I'm going to nurture the Langston Hugheses in my classroom and

make sure they know that they have a voice in this world and that I do

give a $#!% what they feel and what they think. If I didn't give a $#!%,

then well, I wouldn't (and shouldn't) be a teacher. And for all the

David Colemans out there, well, it scares me that you are making

decisions on behalf of my students and the Langston Hugheses of this

world.

*~*~*~*~*~*

I've been scarred and battered.

My hopes the wind done scattered.

Snow has friz me, sun has baked me.

Looks like between 'em

They done tried to make me

Stop laughin', stop lovin', stop livin' --

But I don't care!

I'm still here!

from "Still Here" by Langston Hughes

Originally posted at A Foodie Bibliophile in Wanderlust

*~*~*~*~*~*

I'm sitting here in my home office on this lazy Sunday afternoon (lazy only because it's midwinter break and I don't have to go to work tomorrow) reading Free to Dream: The Making of a Poet, a biography of Langston Hughes (my favorite poet of all time), and I am struck by his educational background. While Hughes did very well in primary school and high school and was praised by his teachers for his love of learning, Hughes, one of our most celebrated American poets, was a college dropout. His first attempt at college was a failure. He went to Columbia University on his father's dime, and after one year decided that he preferred to read books and attend lectures instead of go to class.

I'm struck by this new piece of information I learned about Hughes today because, by all intents and purposes, he should have been a model student: he loved learning, did well all throughout his K-12 education, and was often recognized for his writing prowess by his teachers and classmates. If that's not a formula for someone who should succeed in college, then I don't know what is.

But that's just it. Education can't be whittled down to a formula - numbers to crunch, multiple choice questions to answer. By today's educational reformers, Hughes would be considered a failure. Politicians would deem him a product of a failed system and no doubt his teachers would be blamed (and perhaps fired) for his inability to understand physics and trigonometry, which were the classes he chose to skip and ultimately drop out of Columbia.

But in the 1920s, Hughes used his passion for writing and poetry to seek out like-minded, accomplished people who took him under their wing and nurtured his passion and talent, which we now know turned him into one of the most beloved writers in all of American history. I continue to wonder how people responsible for making decisions about education today can be so narrow minded and refuse to see past the numbers and into the minds and hearts of our students. While we're busy trying to "race to the top", students' needs and talents are disregarded. (Does anyone else see the irony in the fact that Arne Duncan has deemed "No Child Left Behind" a failure yet, with a name like "Race to the Top", the initiative which he created to replace NCLB, isn't the very nature of a race to leave people behind?)

| |

| Langston Hughes: a CCSS poster boy he is not (photo: Poetry Foundation) |

*~*~*~*~*~*

I've been scarred and battered.

My hopes the wind done scattered.

Snow has friz me, sun has baked me.

Looks like between 'em

They done tried to make me

Stop laughin', stop lovin', stop livin' --

But I don't care!

I'm still here!

from "Still Here" by Langston Hughes

Originally posted at A Foodie Bibliophile in Wanderlust

Saturday, March 1, 2014

Is this for real? Please tell me it's not.

A link to Valerie's Strauss's Washington Post blog The Answer Sheet was making the rounds on my Facebook feed yesterday. I was honestly waiting and hoping for someone to refute it and say that it was all some satirical stunt produced by The Onion.

Alas, no one has come forward yet to claim that this is all a hoax:

A video that shows why teachers are going out of their minds

I would have paid money to see/hear someone in that room say, "Are you seriously for real? I wouldn't teach my students this way and I can't believe you have the audacity to stand here and patronize professionals this way. We're closing schools left and right, yet the district paid to fly you here and treat us like children? Peace out."

I weep for my profession, I really do. When was it decided that teachers didn't deserve to be treated like professionals? That our voice deserves to be disregarded? Instead of all the top-down bureaucracy, we need to start thinking about a bottom-up grass roots revolution. We need to find a way to make this happen.

Alas, no one has come forward yet to claim that this is all a hoax:

A video that shows why teachers are going out of their minds

I would have paid money to see/hear someone in that room say, "Are you seriously for real? I wouldn't teach my students this way and I can't believe you have the audacity to stand here and patronize professionals this way. We're closing schools left and right, yet the district paid to fly you here and treat us like children? Peace out."

I weep for my profession, I really do. When was it decided that teachers didn't deserve to be treated like professionals? That our voice deserves to be disregarded? Instead of all the top-down bureaucracy, we need to start thinking about a bottom-up grass roots revolution. We need to find a way to make this happen.

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)